Mark Poynting,Climate researcherand

Erwan Rivault,Senior data designer

Getty Images

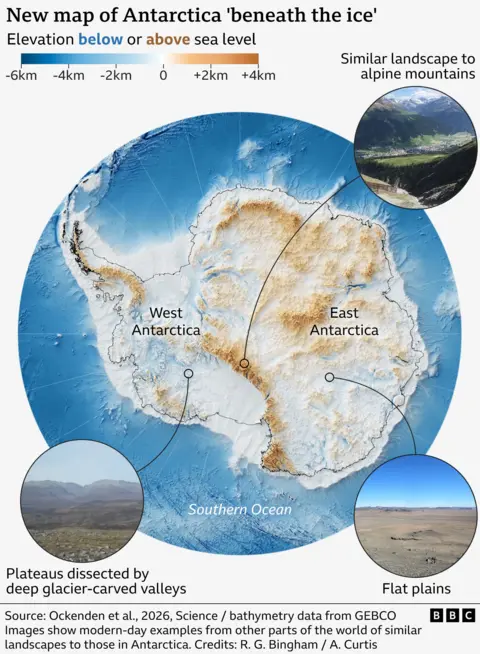

Getty ImagesA new map has unmasked the landscape beneath Antarctica’s ice in unprecedented detail, something scientists say could greatly enhance our understanding of the frozen white continent.

Researchers used satellite data and the physics of how Antarctica’s glaciers move to work out what the continent might look like beneath the ice.

They found evidence of thousands of previously undiscovered hills and ridges, and say their maps of some of Antarctica’s hidden mountain ranges are clearer than ever before.

While the maps are subject to uncertainties, the researchers believe the new details could shed light on how Antarctica will respond to climate change – and what that means for sea-level rise.

“It’s like before you had a grainy pixel film camera, and now you’ve got a properly zoomed-in digital image of what’s really going on,” lead author Dr Helen Ockenden, a researcher at the University of Grenoble-Alpes, told BBC News.

Thanks to satellites, scientists have a good understanding of Antarctica’s icy surface – but what lies beneath has remained more of a mystery.

In fact, more is known about the surface of some planets in our Solar System than much of Antarctica’s “underbelly” – the topography beneath the ice sheet.

But researchers now have what they believe to be the most complete, detailed map of that underbelly ever made.

“I’m just so excited to look at that and just see the whole bed of Antarctica at once,” said Prof Robert Bingham, a glaciologist at the University of Edinburgh who co-authored the study. “I think that’s amazing.”

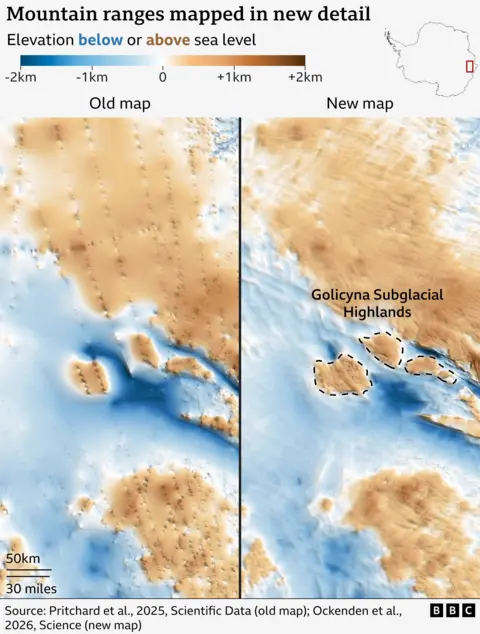

Traditional measurements from the ground or air have used radar to “see” beneath the ice – which is up to three miles (4.8km) thick in places – often along individual survey lines or tracks.

But these tracks could be tens of kilometres apart – leaving scientists to fill in the gaps.

“If you imagined the Scottish Highlands or the European Alps were covered by ice and the only way to understand their shape was the occasional flight several kilometres apart, there’s no way that you would see all these sharp mountains and valleys that we know to be there,” said Bingham.

So the researchers used a new approach, combining their knowledge of the ice surface from satellites and their understanding of how the ice moves from physics – and checking them against those previous tracks.

“It’s a little bit like if you’re kayaking in a river, and there’s rocks underneath the water, sometimes there’s eddies in the surface, which can tell you about the rocks under the water,” explained Ockenden.

“And ice obviously flows very differently to water, but still, when the ice is flowing over a ridge or a hill in the bedrock […] that manifests in the topography of the surface, but also in the velocity as well.”

While we knew about Antarctica’s major mountain ranges, the scientists’ new approach has revealed tens of thousands of previously undiscovered hills and ridges, as well as greater details around some of those mountains and canyons buried under the ice.

“I think it’s just really super interesting to look at all these new landscapes and see what’s there,” said Ockenden.

“It’s like when you see a map of topography on Mars for the first time, and you’re like, ‘whoa, this is so interesting, this looks a bit like Scotland,’ or ‘this looks like nothing I’ve ever seen before’.”

One intriguing discovery is a deep channel incised in Antarctica’s bed in an area called the Maud Subglacial Basin.

The channel is on average 50m deep, 6km wide and runs for nearly 400km (about 250 miles) – roughly the distance from London to Newcastle as the crow flies.

The researchers’ new map is unlikely to be the final one. It relies on assumptions about exactly how ice flows which, like any method, comes with uncertainties.

And much remains to be discovered about the rocks and sediments that lie beneath the ice.

But other researchers agree that, combined with further surveys from the ground, air and space, the maps are a valuable step forward.

“This is a really useful product,” said Dr Peter Fretwell, senior scientist at the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge, who was not involved in the new study but has been extensively involved in previous mapping.

“It gives us an opportunity to fill in the gaps between those surveys,” he added.

A more detailed understanding of all of the ridges, hills, mountains and channels could improve computer models of how Antarctica might change in future, the researchers say.

That is because these landforms and features ultimately shape how fast the glaciers above move, and how quickly they can retreat in a warming climate.

And that is important because the future speed of melting in Antarctica is widely considered to be one of the biggest unknowns in climate science.

“[This study gives] us a better picture of what’s going to happen in the future and how quickly ice in Antarctica will contribute to global sea-level rise,” agreed Fretwell.

The study is published in the academic journal, Science.